King Cove

Area Description & History

King Cove (also known as Agdaaĝux̂in Aleut) is located on the south side of the Alaska Peninsula, 18 miles southeast of Cold Bay and 625 miles southwest of Anchorage. It is located in the midst of a storm corridor, which often brings extreme fog and high winds. Historically, the Aleut people, the original inhabitants of the island, harvested salmon, cod, herring, and other species around King Cove. Subsistence harvest continues to be important among the island’s Native population today. Unangam tunuu was the language traditionally spoken, however, today only about 109 individuals speak this language.1 In 1911, Pacific American Fisheries built a salmon cannery, and in 1949, the city of King Cove was incorporated. The first settlers were Scandinavian, European, and Unangan fishermen. Year round residents are largely Aleutic, with a large influx of temporary workers in March and again in June and July, driven by seafood processing employment. King Cove was included under the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), and is federally recognized as a Native Village. The Agdaaĝuxˆ Aleutian Pribilof Islands Association is the main Native Association active there today.

Infrastructure & Transportation

King Cove is accessible only by air and sea. A state-owned 3,360 foot gravel runway is available for flights. The State Ferry operates monthly between May and October, and uses one of three available docks. A deep water dock is also operational. The North Harbor provides moorage for 90 boats, and is ice-free all year. A new harbor and breakwater is under construction by the Corps of Engineers and Aleutians East Borough. Once completed, a new harbor will be operated by the City, and will provide additional moorage for 60′ to 150′ vessels.2 According to the municipality, all King Cove residents are connected to a water pipeline supplied by Ram Creek. King Cove is one of the leaders of renewable energy in rural Alaska, and 2020 marked 25 years of hydroelectric power for King Cove hydroelectric facilities on the Delta Creek and more recently, the Waterfall Creek hydro facility coming online in 2017. The landfill is nearing capacity with plans to expand solid waste infrastructure from a USDA grant announced in 2018.3 The landfill is nearing capacity with plans to expand solid waste infrastructure from a USDA grant announced in 2018.4 There is one local health clinic. There is one school in King Cove and enrollment has decreased by 32.7% from 2008-2021, but increased in 2022 to 77 students (up by 12% from the previous year). In 2023, enrollment dropped slightly (3%).

Demographics

| Demographics | |

| Population | 874 |

| Population in group housing | 452 |

| Median household income | $79,844 |

| Housing units | 395 |

| Percentages | |

| Male | 58.8% |

| Female | 41.2% |

| White | 12.6% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 49.3% |

| Black or African American | 0.3% |

| Asian | 23.0% |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.0% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 4.8% |

| Below poverty line | 12.8% |

| High school diploma or higher | 82.9% |

| Population under 5 | 3.3% |

| Population over 18 | 81.4% |

| Population over 65 | 11.8% |

| Source: US Census Bureau American Community Survey 5-year estimates (2018-2022) | |

| Population and group housing estimates sourced from Alaska Department of Labor, 2023 | |

Current Economy

King Cove’s economy has depended almost entirely upon year round fishing and seafood processing. It is home to Peter Pan’s largest processing facility, which has historically processed king crab, bairdi and opilio tanner crab, pollock, cod, salmon, halibut and black cod. After announcing partial seasonal closure, Peter Pan Seafoods announced in January 2024 that it would close its King Cove facility for the 2024 fishing season. The company cited cost and cash flow problems, including inflation, rising interest rates, high fuel costs, and financing challenges.5 The plant was the main employer in the community, employing around 500 employees year round. The municipality’s general fund relied heavily on fish taxes and sales taxes relating to fisheries. The facility also provided some city services including heating fuel for residents.

King Cove generated $805,169 in Fisheries Business Tax in 2023 (the most recent available data). This represents a stepwise yearly increase since 2020 (for a total increase of 53% in the past four years); however these data do not reflect the 2024 tax year. According to Shared Fish Tax reports, there was an increase in tax from 2022 to 2023 by 16%. With King Cove’s seafood facility closing in 2024, reported shared fish taxes dropped from $41,386 in 2023 to $19,190 in 2024 (down 116%).

These revenues support basic city services such as education, sanitation, transportation, etc. and are important indicators of community health and wellbeing.

Climate Change Vulnerability and Adaptive Capacity

Exposure to Biophysical Effects of Climate Change

A community’s exposure to the biophysical effects of climate change, which include effects to the biological organisms and physical landscape surrounding them, aids in evaluating their vulnerability. The Aleutian islands are expected to experience increased temperatures and precipitation, and increased summer storm events. Similar to other Alaskan communities, they will be impacted by reduced seasonal sea ice coverage as well.6

In summer of 2023, the Knik Tribe found high levels of paralytic shellfish toxins (PSTs) in shellfish collected from King Cove, Sand Point, and Chignik Lagoon. Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) are increasing in Alaska and are thought to be linked to a changing climate. Several HABs have been detected since. PSP toxins measured in blue mussels, snails, and butter clams collected from King Cove, Sand Point, and Unalaska were frequently above the FDA limit for safe consumption, sometimes as much as 100 times.7 The Agdaagux Tribe of King Cove has their own shellfish monitoring system to reduce the risk associated with HABs and shellfish harvests.8

Dependence on Fisheries Affected by Climate Change

Reliance on fisheries resources affected by climate change can determine how vulnerable a community is to disruption from climate change. Historically, King Cove has been highly engaged with commercial processing within the groundfish and crab fisheries; however the plant closure in 2024 will dramatically affect the community.

Climate-related factors such as warming oceans and changing weather patterns have been noted by residents as affecting their harvests of salmon in particular.9

As climate driven effects on fisheries continue, King Cove residents will be vulnerable to disruptions in livelihoods and subsistence activities. Climate effects on fisheries may cause broader social disruption given the community’s high reliance on commercial fishing and subsistence activity.

Local Adaptive Capacity

King Cove overall has very high limitations on its adaptive capacity. This rating accounts for factors in the community which can make it more difficult to adapt to climate driven disruptions. King Cove’s high rating is due to housing and infrastructure being moderately to highly vulnerable, medium poverty levels, a portion of the population who are more vulnerable to shocks and disasters. In addition, the FEMA National Risk Index identified that the Aleutians East region has very low levels of community resilience.10 King Cove residents have limited capacity to adapt to climate risks and recover rapidly.

| Social Indicators for Fishing Communities* | |

| Labor Force | LOW |

| Housing Characteristics | MED-HIGH |

| Poverty | MED |

| Population Composition | HIGH |

| Personal Disruption | MED |

| *Source: NOAA Fisheries Office of Science and Technology. 2019. NOAA Fisheries Community Social Vulnerability Indicators (CSVIs). Version 3 (Last updated December 21, 2020). https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/socioeconomics/social-indicators-fishing-communities-0 | |

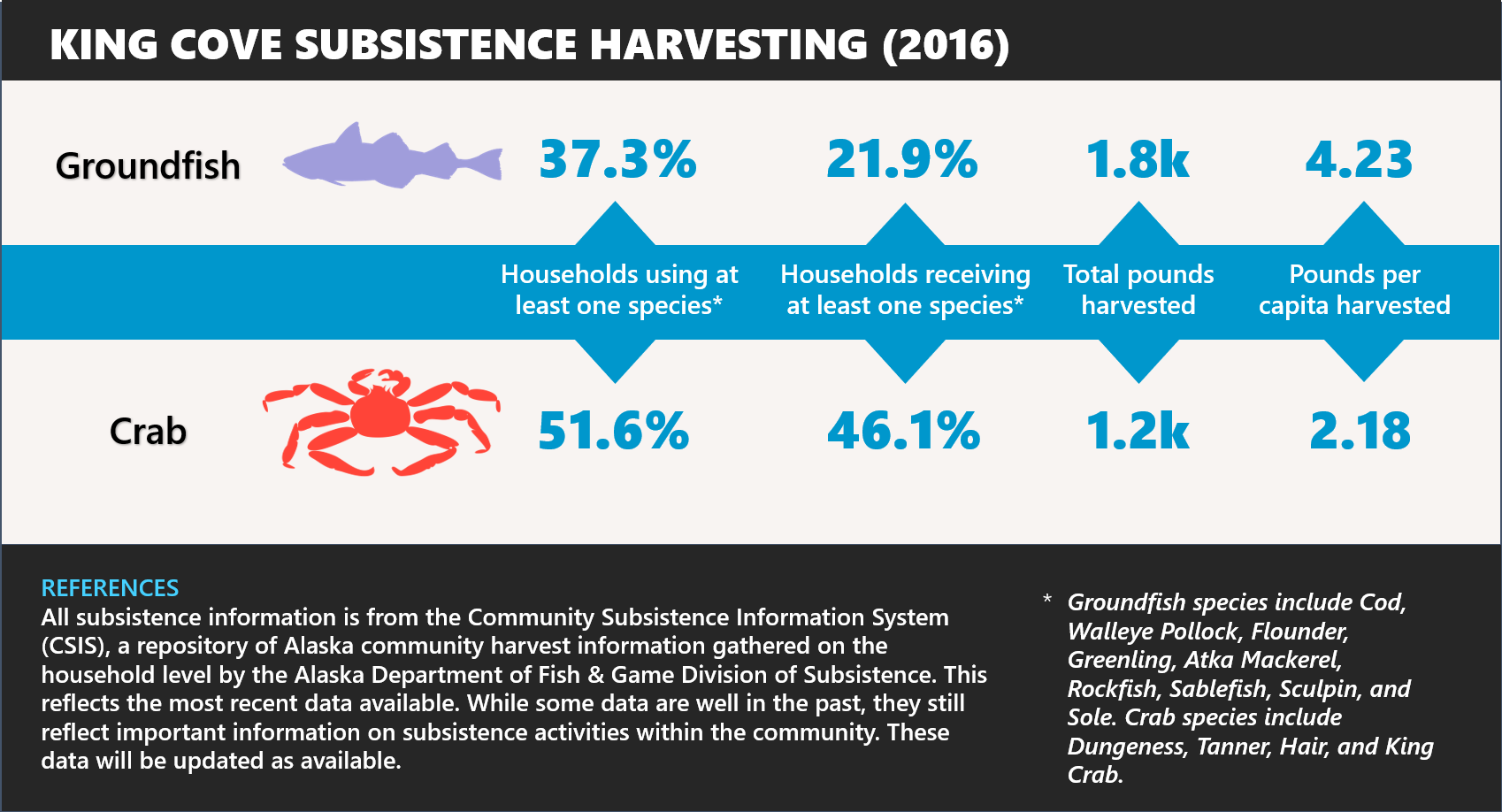

Subsistence Harvesting Engagement

Historically, subsistence harvesting engagement is high in King Cove (salmon and shellfish in particular), and moderately high for groundfish and crab species. Residents gather foods like clams, mussels, sea urchins, chitons, seaweeds, greens, and herbs from the intertidal zones.11 Reliance on subsistence may increase to support food security concerns with the closure of commercial seafood processing; however, recent years have shown declines in key subsistence fisheries. Subsistence halibut shows a steady decline in both the number of fish harvested and the number of active SHARC permits since 2004. Salmon subsistence (in all species) shows a decline in both active subsistence permits and the estimated number of salmon harvested.

Overall, subsistence activities play a very important role in cultural characteristics and food security.Residents of King Cove are engaged in halibut and salmon subsistence fishing. A study conducted by the Alaska Sustainable Salmon Fund in 2016 showed that the harvesting, processing, sharing and consumption of salmon, especially sockeye, was culturally essential for King Cove residents.12 While many residents still used traditional subsistence methods, many households also met their subsistence needs by removing salmon for home use from their commercial harvests. In King Cove, nearly all households (91%) were found to use salmon, with 75% attempting to harvest and 59% receiving salmon from others.13 Overall, it was the most widely utilized wild resource by harvested weight. Changes and weather patterns, rising sea levels, and warming oceans were some of the environmental factors which had recently impacted residents’ ability to harvest salmon. However, economic and social factors, such as access to funds to buy equipment and the influence of local canneries, also affected residents’ harvest patterns.14

APICDA. (n.d.). Aleut Culture. Retrieved November 8, 2024 from https://www.apicda.com/communities/aleutculture/↩︎

City of King Cove. (n.d.). About King Cove Alaska. Retrieved November 14, 2024 from https://cityofkingcove.com/about-king-cove-alaska/.↩︎

Chase, J. (2023, January 23). Small hydro reduces diesel dependence in Alaska. National Hydropower Association. Retrieved November 8, 2024, from https://www.hydro.org/powerhouse/article/small-hydro-reduces-diesel-dependence-in-alaska/↩︎

Huff, Jessie. (2018). USDA Helps Improve Solid Waste Infrastructure for the City of King Cove. USDA Rural Development. U. S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.rd.usda.gov/newsroom/news-release/usda-helps-improve-solid-waste-infrastructure↩︎

McDermott, C. (2024, January 12). Peter Pan’s King Cove plant will stay shut this winter. KDLG. https://www.kdlg.org/fisheries/2024-01-12/peter-pans-king-cove-plant-will-stay-shut-this-winter↩︎

Markon, C., S. Gray, M. Berman, L. Eerkes-Medrano, T. Hennessy, H. Huntington, J. Littell, M. McCammon, R. Thoman, and S. Trainor, 2018: Alaska. In Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II [Reidmiller, D.R., C.W. Avery, D.R. Easterling, K.E. Kunkel, K.L.M. Lewis, T.K. Maycock, and B.C. Stewart (eds.)]. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA, pp. 1185–1241. doi: 10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH26.↩︎

National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science. (2020, November 2). NCCOS supports Alaska Native efforts to detect paralytic shellfish toxins in Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula. NOAA. Retrieved November 8, 2024, from https://coastalscience.noaa.gov/news/nccos-supports-alaska-native-efforts-to-detect-paralytic-shellfish-toxins-in-aleutian-islands-and-alaska-peninsula/↩︎

Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. (n.d.) Climate Change. Retrieved November 8, 2024 from https://www.anthc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/11ClimateChange_2012-2.pdf.↩︎

Aleutian & Bering Climate Vulnerability Assessment. https://legacy.aoos.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/Unalaska-workshop-9.18.14-with-results-and-note-3.pdf↩︎

Federal Emergency Management Agency. (n.d.). National Risk Index: Aleutians East Borough, Alaska. Retrieved November 13, 2024, from https://hazards.fema.gov/nri/report/viewer?dataLOD=Counties&dataIDs=C02013↩︎

Bureau of Indian Affairs. (n.d.). Alaska subsistence program. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved November 8, 2024, from https://www.bia.gov/service/alaska-subsistence-program#:~=The%20Branch%20of%20Fisheries%2C%20Wildlife,natural%20resources%20for%20subsistence%20uses.↩︎

Alaska Sustainable Salmon Fund. (n.d.). Subsistence Salmon Fishery Harvest Monitoring in Cold Bay, King Cove, and Sand Point. Retrieved November 8, 2024, from http://akssf.org/default.aspx?id=3444#:~:text=Point%2C%20March%202017-,Subsistence%20Salmon%20Fishery%20Harvest%20Monitoring%20in%20Cold%20Bay%2C%20King%20Cove,in%20the%20Alaska%20Peninsula%20Area↩︎

Alaska Sustainable Salmon Fund. (n.d.). Subsistence Salmon Fishery Harvest Monitoring in Cold Bay, King Cove, and Sand Point. Retrieved November 8, 2024, from http://akssf.org/default.aspx?id=3444#:~:text=Point%2C%20March%202017-,Subsistence%20Salmon%20Fishery%20Harvest%20Monitoring%20in%20Cold%20Bay%2C%20King%20Cove,in%20the%20Alaska%20Peninsula%20Area↩︎

Alaska Sustainable Salmon Fund. (n.d.). Subsistence Salmon Fishery Harvest Monitoring in Cold Bay, King Cove, and Sand Point. Retrieved November 8, 2024, from http://akssf.org/default.aspx?id=3444#:~:text=Point%2C%20March%202017-,Subsistence%20Salmon%20Fishery%20Harvest%20Monitoring%20in%20Cold%20Bay%2C%20King%20Cove,in%20the%20Alaska%20Peninsula%20Area↩︎